ANECDOTES

When I first began training in TCC (1986), I began hanging around with a fellow, who did Iron Palm, Praying Mantis, bone-hardening exercises (I kid you not: I saw this guy demonstrate this one day, pounding his shins and forearms against a good sized tree, pounding away at it with enough power to shake the bloody thing). Sparring with him was, well, out of the ordinary. My first training was in karate: so when I’d block his blows, it was like hitting my arms with an iron bar. We began training together. I learned (the hard way!) not to counter force with force: it was painful. One night, he said to me: “Let me show you something.” (Note: this was after many months of hard-core training in TCC.) He launched a barrage of blows, which I simply tapped all aside. “Hmmm,” he said. “Maybe you should stick to Tai Chi.”About a year into our friendship, and impromptu training sessions (he worked at a vacuum-cleaner store), he was giving a primer for this young fellow who was going to train with his sifu. While the two of them were bouncing around, flipping over, doing whatever external stylists do, I simply practiced my TCC form 3 or 4 times. I’d started doing Tui Shou (Push hands) some months before. After the 3 of us had finished, my friend made a remark: “At least we broke a sweat.” “What I love about Tai Chi,” I told them, “is that all it takes is a small push,” I stepped in, barely touched my friend, and off he sailed, into a group of vacuum-cleaners 3 yards away in a corner, sprawling. “Are you okay?” I asked, startled. “I’m fine,” he replied. All was cool. But I never heard that remark again. I’m very, very careful now, not to push someone playfully. They tend to go sailing, or are propelled at least 3 or 4 yards away.Years later, I was training with an instructor. Again: “Let me show you something.” Shower of blows. I deflected them all.Somewhere within that timeframe, I was living in Livermore, and this lady I knew (semi-acquaintance) was visiting one of my roommates. She’d gained some weight, and I made one of my famous cracks. She immediately jumped up, and attempted to slap the crap out of me. I used Cloud Hands, tapping each one aside, laughing all the while. After a couple of minutes, she gave up in disgust.Once, I was helping my mother’s boss move some furniture. They had a Tacoma truck, with one of those Leer shells. The shell door was up, I was bent over the tail, down came the door. Without even knowing what was happening, I simply moved my upper body horizontally away and up, the door missing me completely.One night, walking down Amador Valley Parkway in Dublin, past the Jack in the Box, I began to move in a circular manner, thinking to myself, “What the hell…?” Once I completed the intricate pirouette, I looked down. Someone had torn a sprinkler pipe in the bushes from its mooring, and pulled it out so most folks would either trip on it, or bark their shins. One night, at a friend’s house, I was talking to a married couple. The guy had been training in TKD. His wife was seated. He launched into an attack (kicks and punches? I think so). I stepped to one side, and touched him ever so slightly. The result? Hysterical. He sprawled all over his seated wife, who hollered at him about it as they tangled up.Once, a gal I worked with at a mini-mart, saw me walk in, yelled my name, came at me in a straight line fists pumping (she was a large woman, and more than a little odd). I closed my eyes, shifted my weight into my back leg, turned ever so slightly, and moved her with my finger. When I opened my eyes, she was standing off to my right, deflected elsewhere, and facing away from me. “Wow, you must do karate or something!”Once, a friend of mine with a drinking problem, got a little too rowdy. He wanted me to demonstrate push hands. I tried, he got way out of hand. Small guy, too. I must’ve bounced him off the wall a dozen times. His poor beleaguered mom kept picking up the pictures that were knocked onto the floor as I apologized profusely.I sparred this one young fellow in Livermore. This cat, I kid you not, could leap up in the air, sailing horizontally, doing what’s called a Butterfly kick, his aerials were something to behold. We almost clinched; I sent him sprawling 4-5 yards away. After about 5 years into TCC, I began to shop around a little. I went to a famous instructor in Berkeley. I didn’t tell anyone I’d ever done TCC. The first week, we did Tui Shou. Now, I’d been doing fixed-step push hands all this while: this teacher told us to step into the push. I was paired off with this one fellow, a few inches shorter than me, but far wider and more muscular. Each time I stepped into the push, he bounced off a wall. Got a lot of strange looks at that, you betcha. Some months later, I was asked (rather, told) that I’d had prior training, to which I agreed. At the Berkeley kwoon, one night an apprentice and I were practicing, he kept trying to throw me, but my root was too strong: he actually YELLED at me to fall down. Another night, we were doing some Pa Kua exercises with the Tui Shou: my partner was a smaller fellow; he literally ROLLED across my right arm to my left. Got into it with this young chap one day, same place. Fella claimed he was a Hapkido Black Belt. We were doing an exercise that specifically called for a reactive response: instead, he kept trying this one technique, over and over again. I explained to him that’s not what we were supposed to do. He ignored me, kept doing it. I lost my temper (perhaps), or we got into it: next thing I know, we’re on the floor; I have the scissors hold (both my hands trapping one arm, both legs trapping the other) on him. Couple of years ago, I was napping on the BART, on my way home from work. The person seated next to me barely brushed my duster jacket, and I snapped awake.

PRACTICING IN PUBLIC PARKS: TAI CHI IN THE REAL WORLD

It is a common enough sight in this day and age: elderly Chinese people practicing Tai Chi, Qigong, and occasionally other Asian martial arts in a public park. This article is a general guideline to the do’s and don’ts that apply to doing your form in public. The reader will find there are only a few don’ts, and the dos are fairly common sense. I will elaborate based on my own experiences, both positive and negative, in respect to this. Dos:

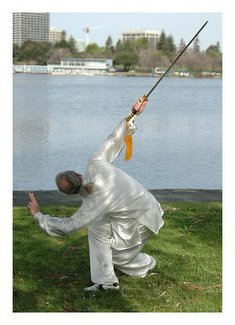

1. Practice with groups, if you can.I practice a full set of every form I do. This consists of the 24 Yang, the 37 Cheng Man Ching form, the 42 Compulsory, the 42 Fu, the Chen forms 1 and 2 (Xin Jia New Frame), a 108 Fu style, the Chen spear, broadsword and sword. Ergo, unless I go to the Lake Merrit Bart station in Oakland, CA., I am going to have issues finding people who do these sets. Groups are a good thing: they give you a sense of flow and interaction. Also, there is strength in numbers: see DON’T # 2.

2. Practice by yourself.It is very common for everyone, at first: you feel your form is not very good, you’re self-conscious, people will stop and stare, make comments (good and bad), etc. The best advice here is: just get over it. There are numerous reasons for this. When I first started teaching, it was at a college in S.F that had been converted over from a Greyhound Bus hangar. Ergo, it was huge, and the area I taught in was towards the back, and anyone entering the school could very clearly see (albeit from a distance) myself and any other students learning, practicing, etc. I was very self-conscious at the start, but one gets used to this sort of thing. First and foremost, you are practicing an art form, and while you should be practicing it primarily for your own personal advancement, art that goes unseen becomes less an art than that of self-illusion and self-aggrandizement. People need to see you in order to appreciate the amount of work and sacrifice that you’ve put into your chosen hobby/path. Secondly, if you are easily distracted by the presence of other people, their watching, commenting, etc., then your focus and concentration is not very good. I have practiced many times at the Lake Merrit Bart when the Lion Dancers are pounding away on drums. It helps keep me focused. Alternately, when you are competing in a tournament, there is always a certain amount of background noise that accompanies the competition, inasmuch as there are usually several events taking place simultaneously. Thirdly, it is far too easy to bail out on practice simply because you have no one to practice with. Practicing by yourself, and sticking to it, will not only help you improve, it will eliminate yet one more excuse you can give yourself. Fourthly, it exposes you to a public view, and you may very well meet other people who are interested, and/or are practitioners as well.

3. Environment.It has been observed (in writing), that the best place is in a park. Why is this? Surrounded by trees (extra oxygen), and the removal of that 60 Megahertz buzz that accompanies us in most cities lends to an Alpha-like state that aids the practitioner in his/her practice. I have discovered a number of suitable areas where I live. The normal advice is this: find somewhere removed from society at large (in re: pollution, you don’t want to inhale car exhaust, do you?), surrounded by trees (optimally: but grassy areas are fine), away from windy, wet environments (this becomes difficult, especially in the multiple micro-climatic areas of the S.F Bay area), away from excessive noise (again, difficult occasionally, as you are in a public park, and are in a position of sharing it w/humanity). It whittles down to this: quietude. Don’ts:Bear in mind, these are rules of thumb, only. 1.

Things to avoid before and after practice:- Eating

- Smoking

- Drinking alcohol

- Sex.

These, again, are only general guidelines. Bear in mind that Tai Chi (and some qigong) are Taoist practices, and because we are human (and some of us have very little time on our hands as is), none of these are written in stone. For instance, the 4 items listed above are generally to be avoided an hour before, or an hour after. At one juncture in my life, I held 2 jobs, and went to school fulltime as well. But I still made the time to practice at least 10 minutes a day. So I had little choice but to come home, devour something right before bed, and practice. Eating immediately before or after any workout is generally advised against. The sexual advice applies primarily to men, as men are supposed to refine their jing (essence), and women are supposed to nourish the blood. Alcohol and tobacco are bad ideas, since Tai Chi and qigong open up circulation, lungs, meridian points, etc. Again, your humanity comes first.

2. Practicing in the afternoon.Now, this seems silly at the onset, because A. it’s recommended to practice Tai Chi or qigong at dawn and dusk (human light cycles), and B. it has been observed that afternoons are when your body is actually more stretched and limber. But this is primarily focused on the neighborhood/area of your park. Originally, I was a late riser, not given to mornings. I read somewhere that Traditional Chinese Medicine considers oversleeping a sign of a corrupted spirit. This was also coupled with some negative experiences. Once, while I was at a Hayward park, I was practicing my form, someone began yelling about “You think you’re so cool, doing that crap! You better leave,” called me names, threatened me, etc. For a while, I would go down to the San Leandro Marina and practice in the afternoons, and encountered similar situations, where some teenagers let the testosterone do the talking. One incident occurred where I was doing a long form, and 2 women w/a child, pushing a stroller, began to make loud, stupid comments. They had a camcorder, and began to film their foolish efforts at belittling me (and probably sent it off to America’s funniest home videos, thinking themselves utterly hysterical, when in fact they were just showing how ignorant and unfunny they truly were). I ignored them, and it was a minor annoyance, which didn’t interrupt my form’s flow. As of this writing, no one has tried to lay hands on me. Bear in mind, I am a middle-aged, well-sized white male, which makes this an Alpha Wolf issue. Women are less likely to encounter a ‘kick school’ mentality, as females are by far more sensible than males in this regard (depending on the neighborhood, of course). I spoke to my Sifu, Dr. Johnny Jang, one day, in this regard, and he stated that he’d had one issue about this in over 30 years of teaching. Of course, most of the idiots who would do this sort of nonsense probably figure it’s a bad idea, since the stereotype of the deadly Asian pervades America. (This is not always true: I have heard a story of a famous Tai Chi player who had to stop practicing in Washington Square in S.F, because many street people would come up and start fights with him; so it varies demographically). However, getting up early in the morning for practice means you are less likely to encounter this sort of person, as they are usually sleeping off the revelry of the night before. Practicing w/a group also will preempt this sort of behavior

3. Weather conditions.The Chinese speak of something called ‘Wind Evil’, and advise that one should avoid this. Wind carries bacteria, pollution, and other things. This is difficult to avoid if you live in the S.F Bay area (or even in a valley, near an ocean, etc.). Severe cold and heat are other conditions to be wary of, as well as rain, snow, etc. This varies according to individual. While it would be foolish to practice outside in the midst of a tsunami, hurricane, monsoon, or similar circumstances, it is also far too easy to look outside, see a light rain, and say, “Oh, I think I’ll skip it today.” Personally, I thrive in cold weather, and heat makes me sleepy. I have actually practiced in weather so cold that it felt like hundreds of tiny needles poking into my fingers. But by the 3rd or 4th form, my hands have warmed up sufficiently, and by the end of my routine, so have my feet. When it really starts to rain, I have a park I go to where there are trees that provide somewhat of an umbrella. I still get wet, true, but not nearly as soggy as I would be if I were at my other park where there is no shelter. But if I am out in the open, and there is a sudden deluge, I power through it instead of running for cover, as again, we are in the Bay Area, and more often than not, the deluge is temporary at best. This varies according to individual needs. For example, in the winter, I only go out to practice for about an hour (just because I thrive in cold weather, doesn’t mean I have to be foolish: as Jou, Tsung Wa once observed in his wonderful book, The Dao of Tai Chi, “There is only one warning I would like to give: Although the practice of Taijiquan can promote good health, it cannot help people who do not take care of themselves.”), while during the summer, spring, and autumn months, I go into extra time for practice.

4. Practice areas.This is more of a preference than a DON’T. I prefer hard surfaces (and yes, I do Chen style, which is more likely to cause injury, especially since I tend to stomp very hard). If you prefer grassy areas, that’s fine. If you prefer gravel, or any sort of surface, that’s good too. But I will go out and practice in wet weather, and so my preference makes sense. But it is up to the practitioner. So, in summation, be sensible in your practice. Be careful, use some sense, explore your area, and practice. Tai Chi, like many things in life, renders great rewards for discipline and hard work. As you sow, so shall you reap. Good playing to you all.

TAI CHI CHUAN: SEEKING STILLNESS IN MOTION

It is becoming a more common sight in the San Francisco Bay Area: throngs of elderly Asians performing a softly fluid, slow-motion set of movements in tandem, all of them moving in a choreographic set of postures that is both soothing and graceful at the same time. Anyone who has been to Golden Gate Park in the early morning, or in parks in Oakland has perhaps seen them. And this prompts the question: what is this mysterious set of calisthenics they are doing? Most people can answer: Tai Chi. But what is Tai Chi, exactly? Tai Chi Chuan (alternately spelled Taijiquan) is an ancient exercise that combines the very best of the movement arts, Tuina (Taoist yoga), and Traditional Chinese medicine. Often many forms are composed of a certain set amount of movements (ergo, one will encounter numbers, such as the 24 Yang form, the 37 Cheng Man Ching form, the 36 Chen form, etc.) derived from a specific family legacy (Yang, Sun, Chen, Wu). And while some of these forms vary in appearance, they all carry the movements and principles that characterize Tai Chi. Tai Chi Chuan is a method of meditation, self-defense, an opening of one’s acupressure points (called meridians), health maintenance, a way to improve one’s self awareness, a form of physical therapy (more Western doctors are prescribing Tai Chi not only for elderly patients, but for persons with back and heart problems), a path to spiritual enlightenment, and a relaxation technique, all rolled into one. It is suitable for everyone, regardless of age, body type, or fitness level. The common misconception is that it is easy. The slow, languid movements one sees in its performance misleads the observer. It is primarily a mental discipline, geared toward seeking stillness in motion. It is perhaps one of the most taxing disciplines one can pursue. The data overload from one class is difficult: often the newbie practitioner will be frustrated, not only at their inability to do the postures perfectly the first (or second, or even hundredth time), but also at the multiple mental principles required to even come close to doing the hand forms to a satisfactory degree. But as any adult knows, anything that is worthwhile takes time and effort. As Thomas Paine once said, “That which we obtain too cheaply, we esteem too lightly.” In other words: it takes work. And like all things in this life, what you put into it affects what you receive from it. Whether it is Tai Chi, or a career, any sort of exercise, the practice of anything important is, in short, an art form. Kung Fu literally translates to, “To have skill.” One can apply this to carpentry, to computer programming, to any interest, professional or simple hobby. Because life is, in all its aspects, a work in progress. So try, and see, if Tai Chi suits you. If not, then at least you’ve made the effort, and that is something in and of itself. If so, then you have a long road ahead of you, but one filled with numerous rewards, both mental and physical, and the growth potential for each individual in this art is exponential, contingent on effort made. But it takes work.